“Dark Ages of Technology”: Scattered Thoughts on 40k and History, or, One Weird Trick To Fix 40k (Clerics Hate It!)

Inspired by Weird & Wonderful Worlds’ post on a lighter and softer, more actual-history-inspired take on the Warhammer 40,000 universe, I started thinking about the WH40k universe as a metaphor for history in, perhaps, a more direct and literal way than I had before. And something finally clicked for me.

If you take 40k seriously as a metaphor, there’s a real problem with the end of the DAoT.

Like, you’ve got your classical/antiquity period, with Egyptian Necrons who fade from prominence, pagan Elves, and similarly pagan humans (Romans, albeit the broad idea of “Romans” you’d see in the Medieval period) quasi-worshiping their Men of Stone AI rulers. Then humanity convert to space Christianity, which goes great (for certain definitions of greatness) for a while, but ultimately they end up as the fractured modern Imperium with the thread of succession lost and infrastructure decayed (albeit a bit less fractured than IRL Roman successor states, but they’ve got an eastern/western empire split in recent lore thanks to the Great Rift!)

So far, so true to the standard accounting of European history.

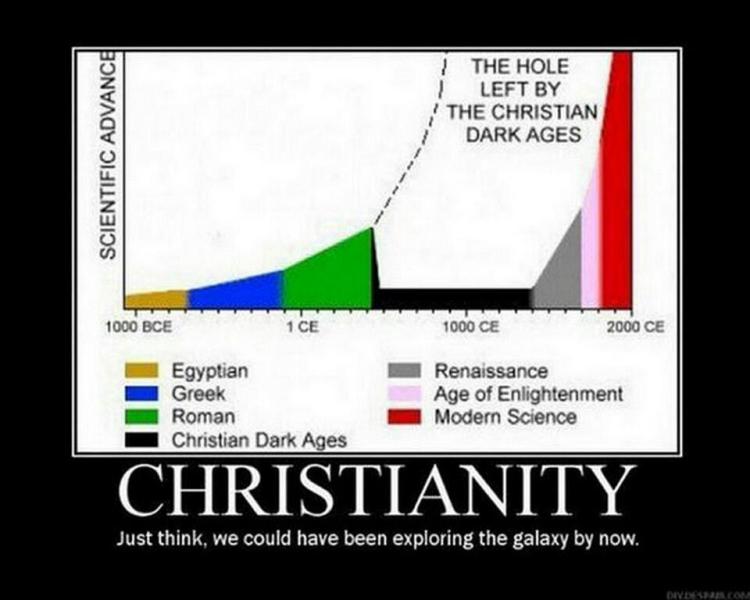

Except, we’re seeing double here. Both the DAoT era and the Great Crusade era are the “”golden age”” of Rome, when civilization was unified and prosperous, that’s collapsed into the current “dark age”. (In both cases, humanity coverts to Space Catholicism only after the collapse, which doesn’t fit with actual history but does fit the pop history of the Christian Dark Ages – once when the Emperor founds the Imperium and again when he quasi-dies and his more secular Imperial Truth is retrofitted into a religion.)

Arguably this reflects an actual confusion that dominates pop history, where the entire latter history of the Roman Empire tends to get fast-forwarded and muddled.

The DAoT ends in what’s almost a parody of the older “decline and fall of the Roman Empire” view (still popular among many conservatives today!): too much gay pagan sex causes the space-lanes to instantly crumble via magic, and civilization immediately collapses. The Great Crusade era ends in, perhaps, a somewhat more prosaic (but still very “fall of the Roman Empire” in its exaggerated importance) battle: infighting among the upper/military class, factions of whom unwisely employ (pagan!) foreign allies alongside their forces, leads to the capital being sacked.

If we were to nudge this closer to real history, my instinct would be to just drop the Fall of the Eldar stuff entirely. No warp storms, no massive disaster the Emperor needs to reunite and rebuild humanity from. After a brief period of being persecuted as a weird cult, the Emperor and his followers rise to power in the DAoT space empire and overthrow (i.e. ban) the old ways of the AI-gods, taking over as the new state religion. By this point galactic human civilization had, objectively, been in decline for some time (in terms of imperial control, but also transport infrastructure etc.) but it managed to hold on for a while afterwards, and if you ask many humans is still hanging on.

Where does cutting their Fall leave the Eldar? The thing is, the canon 40k timeline implies that the Eldar were already pretty marginal on a galactic scale by the time of their Fall, because humanity was busy having a Golden Age where they expand to cover the entire galaxy at around the same time. (The peak of the Eldar Empire in an objective tech/power sense seems to be, canonically, around the end of the War In Heaven long before humans evolved – obviously that doesn’t correspond to anything historical, unless you believe in Atlantis or view it in a more holistic “hunter-gatherers had it better” sense perhaps.) Their Fall pushes them a little further in this direction, but it’s real impact is splitting them into Wood Elves, High Elves, and Dark Elves – I mean, “Exodites”, “Craftworld Eldar” and “Dark Eldar”.

Since the Dark Eldar pretty much are the pre-Fall Eldar (Slaneesh cultists with big cities), and the Exodites are generic anarcho-primitivists, you could justify this split by just saying that the Slaneesh cult gradually gained power in the much-diminished Eldar core and the Craftworld and Exodite Eldar drifted away since they weren’t on board.

But if we’re leaning into the history in our remix and kind of treating the Eldar as stand-ins for what the Romans would have called Barbarians and the Medievals would call Pagans (with some handwaving to allow for other factions to also fill this role sometimes), I don’t really think a strict three-way split is necessary or desirable. Portioning faerie stuff out into three arbitrary categories like that always felt a little weird to me anyway, and the Good Guy/Bad Guy split the Dark Eldar create rubs me the wrong way even in standard 40k, let alone in an attempt at a more “realistic” take. From a human perspective, Eldar are Eldar, unpredictable and fey; and some Eldar would agree that they all basically worship the same Chaos Gods of War, Love etc under different names, while others would quietly titter at the notion that any two Craftworlds represent the “same” “faction” just because they both use spaceships.